Surgical Repair of Cleft Palate and Cleft Lip

Each year in the U.S. about 2,650 babies are born with a cleft palate (CP) and 4,440 babies are born with a cleft lip (CL), with or without a CP.1 Isolated orofacial clefts are among the most common birth defects in the U.S.1

CL is an incomplete fusion of the upper lip, often extending into the base of the nose to include the upper gum and maxilla. Surgical repair is recommended within the first three to six months of life.

CP is the failure of the hard and/or soft palate to fuse to midline during development. Surgery is recommended within the first year of life. Because the lip and the palate develop at different gestational time periods, it is possible to have a CL without a CP, a CP without a CL, or both together.

Subsequent surgeries to optimize the child’s development in breathing, hearing, speech and language may be required. These procedures are offered by three surgeons within the MUSC Children’s Health Craniofacial Anomalies and Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate pro- gram: Krishna G. Patel, M.D., Ph.D., specializes in pediatric facial plastic and reconstructive surgery; Christopher M. Discolo, M.D., specializes in pediatric head and neck surgery; and Jason P. Ulm, M.D., specializes in craniofacial and aesthetic surgery. Together, these surgeons perform an average of 50 new CP and CL repairs every year and hundreds more follow-up surgeries in adults as well as children.

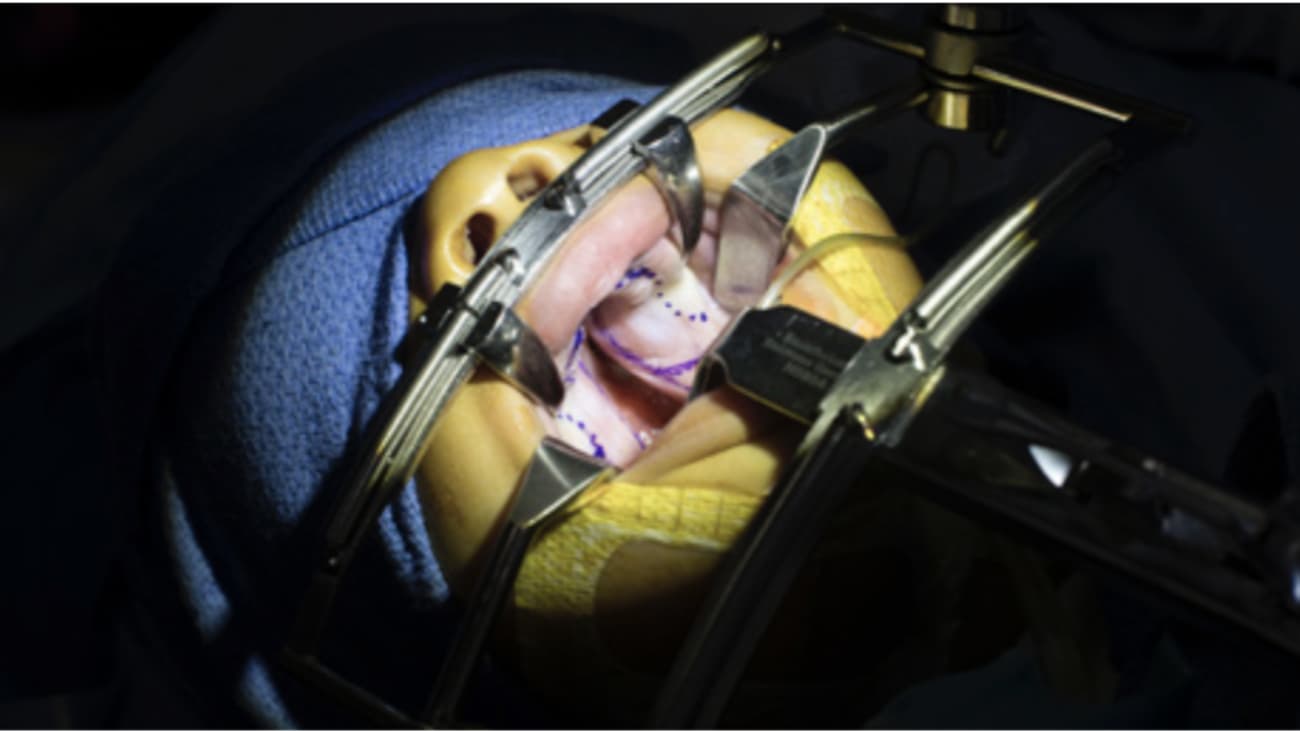

Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate Surgery

The challenge of CL repair is achieving symmetry of the lip contour and the nose. Most often, the lip length on the cleft side is too

short. The most common repair technique, rotation advancement, addresses the foreshortened cleft lip length by first rotating the cleft- sided lip down and then advancing the edges of the cleft together.

One of the challenges of CP surgery is restoring the orientation and function of the soft palate musculature. This abnormally positioned muscle prevents normal palatal function from occurring. The most common consequence of this malfunction is velopharyngeal insufficiency (VPI) which results in hypernasal speech and reduced intelligibility. Proper muscle function maximizes the potential for normal speech outcomes.

To reorient the muscle and prevent VPI, the MUSC Children’s Health surgeons perform one of the more challenging techniques: the CHOP Six Flap modified Furlow Palatoplasty. This technique, offered by few institutions, advances the tissue to the midline to close the cleft in the anterior half of the palate. In the posterior half, the muscle is freed of the abnormal attachments to the hard palate and then rotated 90 degrees and placed into the correct orientation. Rotating the tissues/muscles 90 degrees also allows for simultaneous closure of the cleft in the posterior half of the palate. Unlike other techniques, this approach increases the length of the palate, which is important in enabling clear speech.

Subsequent Surgeries

Oronasal fistula (ONF) is a common complication following CP surgery, occurring in 4 to 35 percent of cases.2 The two main ONF symptoms are nasal regurgitation and speech problems, such as hypernasality. ONF develops primarily because of repair under tension and, in some cases, postoperative infection, especially in adults.

Among children, the ONF rate was found to be 4.9 percent in a 2015 analysis of 11 studies comprising 2,505 children.3 The ONF rate among surgeries performed by the MUSC Children’s Health’s cleft team is less than 1 percent. Repair of ONF is challenging because scarring has often compromised blood supply to the palate. The surgery requires raising multiple tissue flaps to close the fistula.

The MUSC Children’s Health surgeons spend significant time during the primary palatoplasty relieving tension off of the incision line, which decreases the risk of fistula formation. Additionally, strict postoperative guidelines, such as mandating a soft diet and no pacifiers, are followed to decrease the risk of fistulas.

Multidisciplinary Care

The cleft team at MUSC Children’s Health comprises not only specialty and subspecialty trained surgeons, including pediatricians, orthodontists, pediatric dentists, otolaryngologists, oral and maxillofacial surgeons, but also speech-language pathologists, audiologists, genetic counselors, nurse coordinators and social workers. Comprehensive, coordinated care ensures that patients receive their care at the correct time, which lessens their need for future surgeries.

Watch a video of surgical footage narrated by Dr. Patel, visit the Pediatrics page of the MUSC Health Medical Video Center.

References

- Parker SE, et al. Birth Defects Research (Part A): Clinical and Molecular Teratology 2010;88:1008-1016.

- Cohen SR, et al.Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87:1041–1047.

- Bykowski MR, et al.. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2015 Jul;52(4):e81-87.

--LINDY KEANE CARTER

Source: Progressnotes Fall 2018